PROJECT

CPU Simulator

Project Overview

For my computer science course, my final project (before collecting my certification) was to simulate a CPU in Python using Git version control. I decided to make a minimal calculator, but do my best to make the limited features I did implement as good as they could be. So here it is – my embedded calculator CPU project.

I won’t be doing my normal thing of copying and pasting loads of code here, as the point of the project is as much about the internal operation as it is about code. The Github repo is available for you to spy on the code if you want to.

Premise

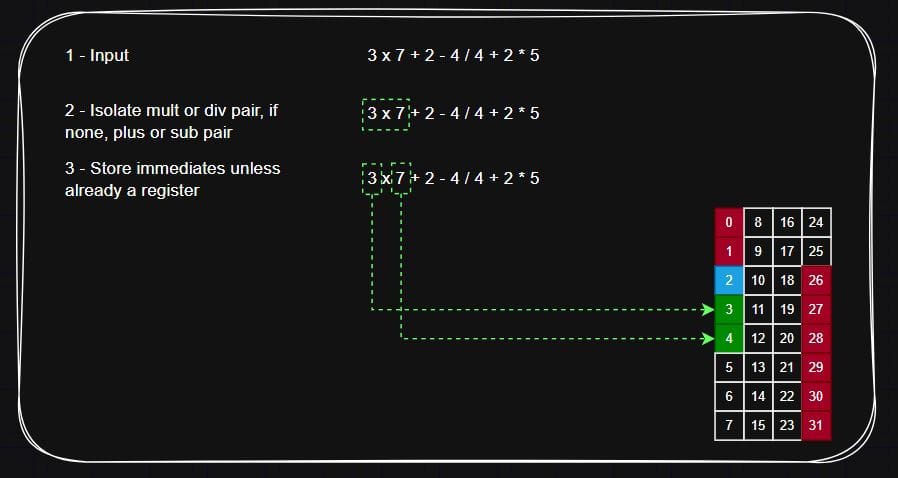

I wanted to create the internal CPU architecture of: control unit, arithmetic logic unit, registers and cache, as well as including RAM. The input would be a plain English text string, something like: 5+3*10-5/2, and the calculator will figure the answer out by breaking it down into sub-equations in the order of operations. The final output will be saved to the calculator’s cache, and if an equation is cached when an input is given, it returns the answer from the cache instead of calculating it again.

The plain English text would be converted into instructions and converted to Assembly. The Assembly would be decoded by the CPU’s control unit, operations orchestrated, and plain English outputted at the end.

Accepted signs were originally meant to be plus (+), minus (-), multiply (*), divide (/) and power(^), but I opted to remove power into the project.

Limitations

This is an extremely basic calculator. It’s not basic in how it’s coded, but it’s basic in operation. The main limitation, besides only allowing for 4x symbols, is that division is floor division in the absence of floating-point numbers. 4/3 will become 1 even though the answer is 1.33.

I also opted not to implement RAM mid-project, as it became clear that the cache served its purpose without needing RAM. Less of a limitation, more of an omission. I did put a good emount of time into learning how I would do this, and I began creating that in my mind, but I decided to not do that in the end.

Architecture

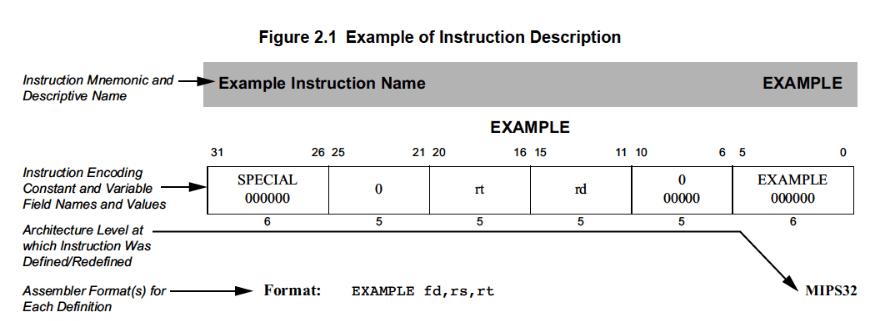

I tried to keep my implementation as close to the MIPS32 guide I have access to.

URL: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/downloads-mips/documents/MD00086-2B-MIPS32BIS-AFP-6.06.pdf

URL: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/downloads-mips/documents/MD00086-2B-MIPS32BIS-AFP-6.06.pdf

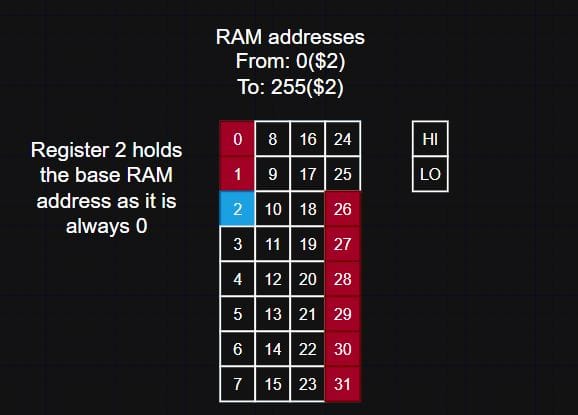

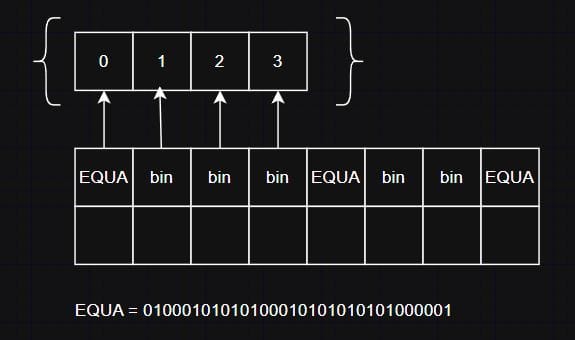

Cache blocks are 32 bits or 4 words in length. The registers contain 32 registers plus a hi and lo register for multiplication and division. I only used the lo register, though. Registers 0-1 are reserved and cannot be used, and the same goes for registers 26-31. Register 2 is reserved for RAM referencing (which I didn’t implement).

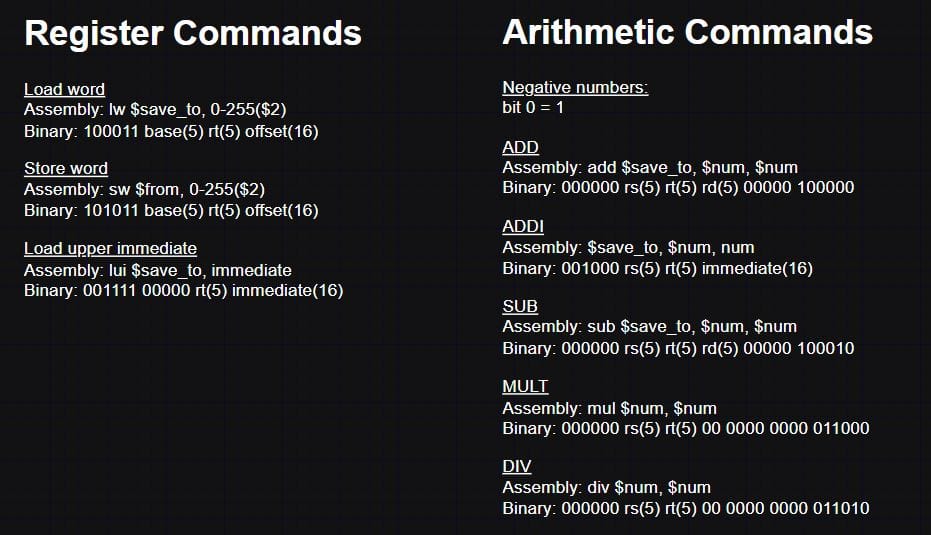

Assembly & Binary

I have always been excited to write some Assembly since I knew it was in the latter portion of my course. The translation of Assembly to binary was made much better by the MIPS32 guide I had access to. The things in this process that I think were most difficult, were being consistent with binary signs (positive and negative integers), remapping the Assembly instructions to the binary format of MIPS32, and keeping the binary to 32 bits when stored and processed.

One thing I struggled with initially was performing basic operations we take for granted: len(), val1 == val2, without using those same functions to return the value. I had to get quite explicit with using pointers, which helped a lot, but I did have to take some liberties in the code here and there to keep myself from going insane while trying to do very basic checks (not always). Store and load word were intentions to manage the RAM, but I didn’t implement RAM in the end.

Multi-part Equation Handling

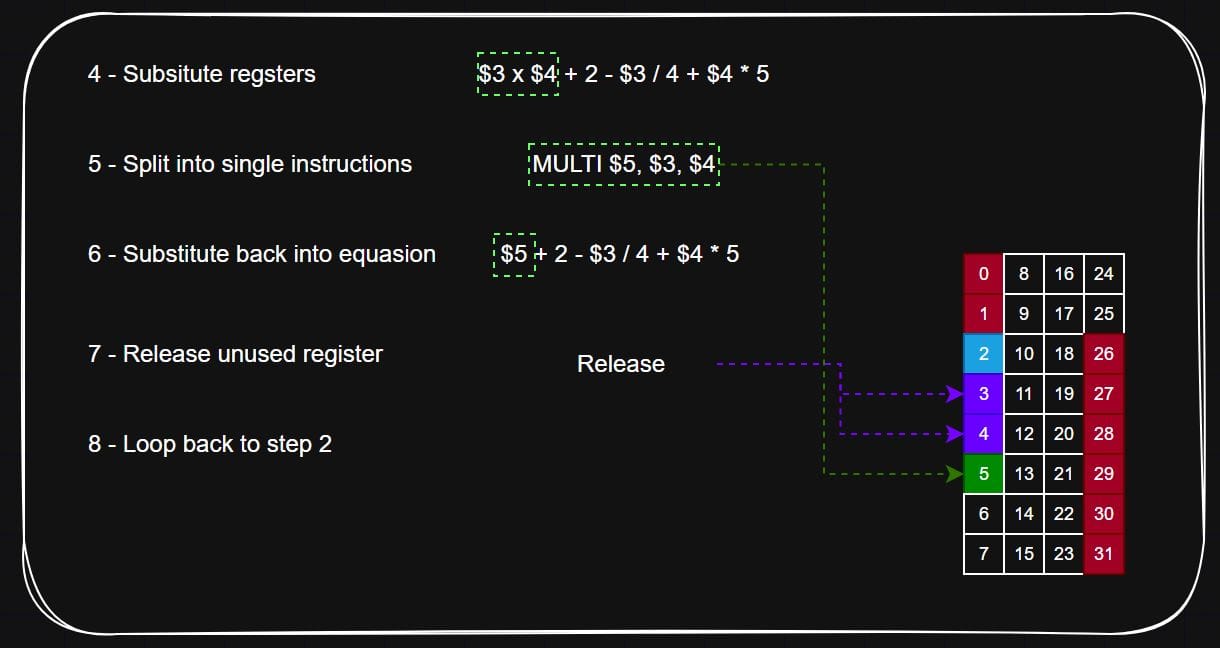

This was the easiest and least intimidating part of the project to complete. The plain English text has all of its spaces removed and each character is regex checked for illegal characters. Then, the equation is split into a list – 5×10 becomes [5, * , 10]. The order of operations is processed one instruction at a time by passing the text to the Assembly script for formatting, and passes that Assembly into the CPU for operation.

Registers

Register replacement is dynamic – after each equation when the result is saved, the registers saved for the sub-equation are released.

Arithmetic

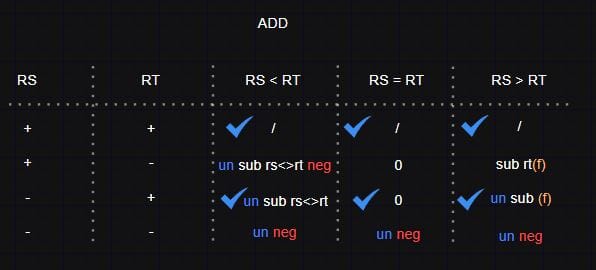

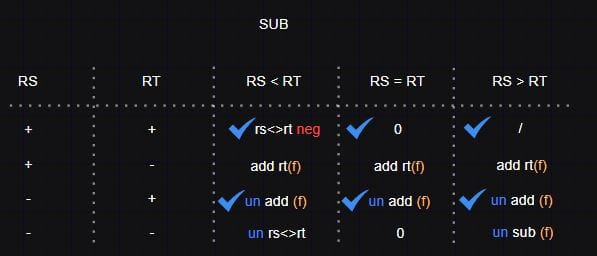

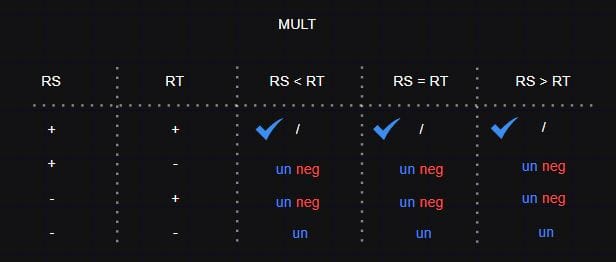

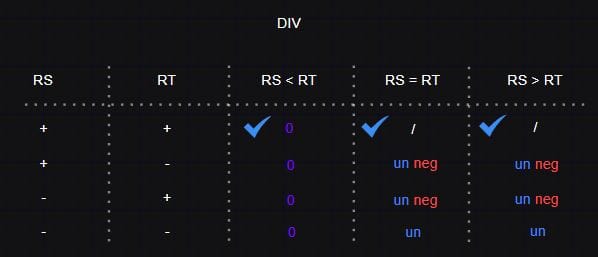

I didn’t realsie the logic for +, -, * and / would be so complex. I made a point to myself to sit down and map out myself how all of the scenarios would work, with number 1 (rs) being smaller, equal to or larger than number 2 (rt) for +, -, * and / when both are positive, one is negative, the other is negative, and both are negative. Most scenarios couldn’t be tested from how the script works, but the ones that could be tested were, and they came out correctly.

A blue tick indicates I was able to test the outcome directly.

un = perform the equasion with unsigned (positive) numbers

neg = the outcome must be enforced as negative

rs<>rt = switching the numbers around, so 1-2 becomes 2-1

(f) = flipping the sign of something. If touching a number rt(f) it means flip the sign of rt, otherwise it means flip the outcome

un = perform the equasion with unsigned (positive) numbers

neg = the outcome must be enforced as negative

rs<>rt = switching the numbers around, so 1-2 becomes 2-1

(f) = flipping the sign of something. If touching a number rt(f) it means flip the sign of rt, otherwise it means flip the outcome

To figure out the logic of all of the arithmetic, I sat down with a book and a pen, and doodled calculations to figure out how the CPU will handle all of the scenarios. It took a while to code, but the logic shoud match the implementation.

For division, I included additional logic to account for division by 1 or -1, and to make the result the opposing number with or without a flipped sign for ease.

Caching

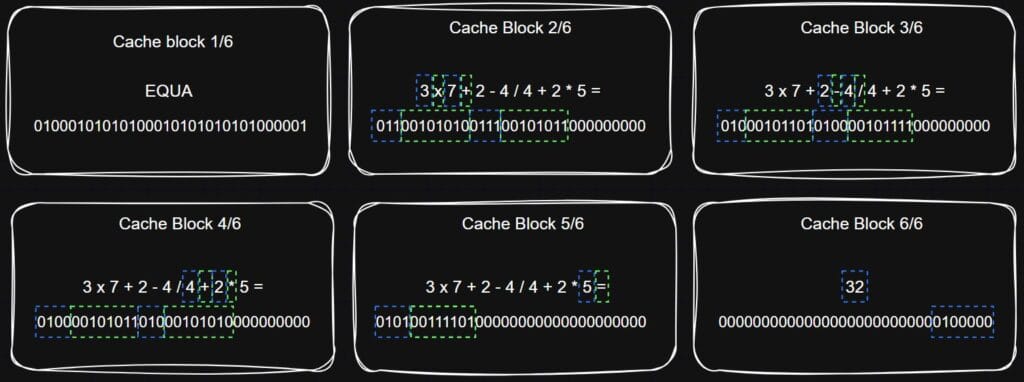

Once an equation is complete, the equation and its result are encoded into cache blocks. It took a while to decide on a safe and reliable, because the program needs to be able to determine when a number starts and a symbol begins, when numbers are preceded with a sign (1, 0) and are of an unfixed length.

Each block is encoded by iterating through the characters of the equation until a block is full, or contains the answer. Each equation block starts with a block that contains “EQUA”, as to be a reference for lookup for when one series of blocks starts and when it ends. Each block that isn’t “EQUA” or the answer, must end in a symbol. If the symbol doesn’t fit at the end (the only number in the block is too large), then the number is left padded with 0’s after the sign.

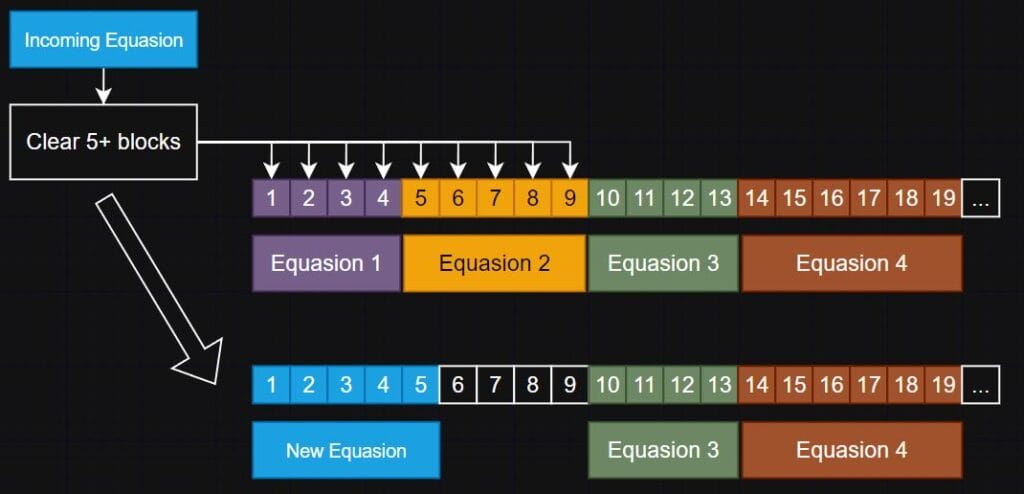

When the cache becomes full (there aren’t enough blocks for the incoming equation), then it executes the FILO replacement policy and removes the nessecary number of blocks, and following blocks until the next “EQUA” block. This prevents cache blocks from becoming fragmented and unreadable.

Summary

In summary, I’m very happy with this. Creating an embedded CPU for a calculator that takes any loaded plain English equation, converts it to Assembly, and passes it to a CPU for operation was challenging, interesting, and worth the effort. I gave my best effort to complete this faithfully to the assignment, made it my own and had fun with it. I can’t say that I’ll be coding in Assembly now, but I have a great deal of respect for those that do, and those who create this kind of architecture.